The electricity market: how electricity prices are set

Electricity customers have been able to freely choose their supplier since Europe’s electricity markets were liberalised around the turn of the millennium. But this doesn’t mean that consumers can choose to be supplied exclusively with wind power or electricity generated in a particular region. Electricity flows are only subject to the laws of physics and they always follow the path of least resistance. This means that power cannot be linked to a specific source once it’s injected into the grid.

That said, customers can be sourced solely with green power – electricity generated from renewable sources. However, to do this, an intermediate step is required. On-balance-sheet electricity trading is carried out independently of physical electricity flows, by means of guarantees of origin. Electricity suppliers procure a certain quantity of power from a generator and receive a guarantee of origin for the purchased energy. These certificates show where the traded electricity was produced and whether it came from a wind park or hydro, solar or thermal generating station. If more and more customers choose green electricity, the price of the certificates rises, which in turn provides an incentive to build additional renewable generating plants.

How electricity is traded

The price that electricity suppliers have to pay on the wholesale market is determined by supply and demand. Often, this is based on a bilateral – or over-the-counter – transaction between a generator and a supplier. But power is also increasingly being traded on electricity exchanges where standardised products such as futures are bought and sold. On the futures market, electricity is traded for delivery over the coming years – this contributes to long-term price stability, both for generators and in the sale of electricity to end consumers. By contrast, on the spot market, long-term plans are optimised on a daily basis, as electricity is traded for delivery either on the same or the next day.

Negative electricity prices

If more electricity is available on the spot market than is required to meet short-term needs, electricity prices can turn negative. In this case, buyers are rewarded for purchasing excess power. This is because supply and demand in the power network need to be precisely balanced at all times, so that the grid remains stable. When too much power is available, negative prices provide a financial incentive to consume electricity in order to reduce the load on the network. Electricity prices are constantly changing and this helps to stabilise the system. Negative prices frequently occur when large quantities of electricity are generated from renewable sources, such as wind or photovoltaic, and at the same time demand is low, for instance on public holidays or during holiday seasons.

How electricity prices for end users are determined

The electricity price that customers pay is made up of three components: the cost of the energy itself, the cost of using the electricity grid, and taxes and levies.

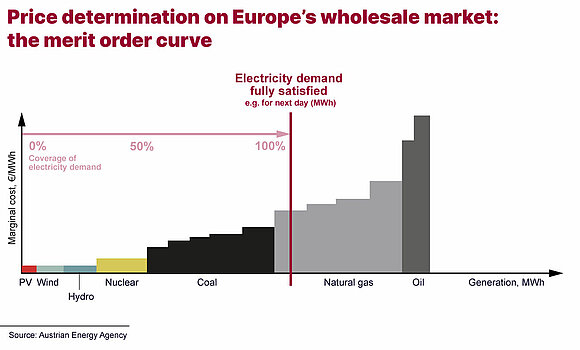

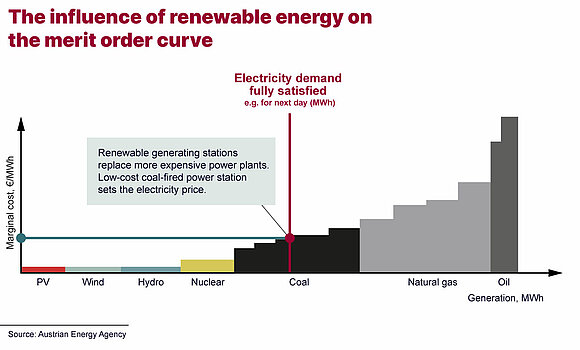

Wholesale electricity prices are determined through the interplay of supply and demand. The distinguishing feature of how electricity prices are set is called the merit order. Power stations are ordered according to their marginal costs – in other words, the costs incurred by generating one additional megawatt hour of power at the power station concerned. The price that all generating stations receive for their electricity is equal to the marginal costs of the last power plant from which electricity is called off in order to meet demand.

Thermal installations such as gas and coal-fired power stations usually determine the price because marginal costs include the price of fuel (like gas or coal) as well as costs for CO2 emission allowances. On the other hand, power stations that produce electricity from renewable sources like wind, water and sun have very low marginal costs. If these producers are in a position to satisfy all or at least a significant proportion of electricity demand, more expensive providers are pushed out of the market – which leads to a fall in electricity prices.

So this mechanism not only ensures that there are sufficient power stations on the market to cover electricity needs in full; it also means that particularly cost-effective electricity producers get the nod before others. And this is especially important from a medium-to-long-term point of view: it gives power station operators a major incentive to cut costs and to invest in renewable generating facilities, because electricity is certain to be called off from installations like these thanks to the reduction in their marginal costs.

Trends in system charges

Extensive changes to the system charges are planned over the coming years. At present, customers pay a relatively low price for capacity, but lots for the energy they actually consume. The aim is to turn this situation on its head. This is a response to the growing significance of high-capacity consumers, such as those in the e-mobility sector. Especially during rapid charging, electric vehicles cause high peak loads that put electricity networks under considerable pressure. In future, consumers who place heavier burdens on the electricity grid will have to pay more, as is already the case with internet rates. This means that anyone who wants to charge their e-vehicle quickly will have to pay a higher tariff. Customers who do not use substantial amounts of capacity will not face any significant increases in system charges.

Flexible tariffs thanks to digitalisation

Digitalisation and the broader rollout of smart meters will pave the way for electricity supplies based on flexible tariffs. This will enable price changes on the electricity exchanges to be passed on directly to final consumers. As a result, customers will be able to use electricity specifically at times when it is cheaper – during the night, for example. This will be a particularly attractive option for users of devices that consume large amounts of energy, such as e-vehicles and heat pumps, which do not require power at a specific point in time; instead, the supply of power to these devices can – in part at least – be shifted to a different time of day.